The Drama of Ethnic Identity

Why African states are not making progress - and what needs to be done.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Why African states are not making progress – and what needs to be done.

In 1963, the Organization of African Unity, a predecessor of today’s African Union, was founded in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa. I was fifteen years old and a student at the local German school. While the students were playing a game, I was approached by a classmate and asked him:

‘Where are you from? What’s your home country?’ When asked the same question, I replied with some astonishment: ‘What’s this question about? I am Ethiopian.’ ‘No, that was yesterday. As of today, you are African,’ said a fellow student. This little anecdote reminds us of how great the euphoria was back then, not just among us students in Addis Ababa but throughout Africa.

Most African countries gained their independence in the early sixties. There were great hopes: unity of the continent, a pan-African future, peace, independence, and economic prosperity. Millions of people all over Africa longed for an upswing and a better life.

Soon, however, there were armed conflicts in the newly formed nations. The triggers were ethnic conflicts between different ethnic groups in some of the 55 countries. When the major European powers divided Africa among themselves in the nineteenth century, they drew the borders of their colonies on the drawing board. They took no account of the history of the respective region or ethnic identities. On the contrary: According to the motto’ divide and rule’, the colonial rulers played the various ethnic groups against each other. They divided large former nations into different tribal territories and fueled the differences between the respective ethnic groups to make them compliant.

Some ethnic groups acquired the favor of the Europeans. They collaborated at the expense of other tribes. Even centuries before, the hunt for enslaved people was a lucrative business for some ethnic groups. Their clients were the slave traders who, between the sixteenth and the nineteenth century, around thirteen million Africans deported overseas. Hatred, envy, and mistrust between the peoples of Africa were fostered over generations. The division of African societies into ethnic groups is the main reason why Europeans were able to conquer the entire continent in less than fifty years.

‘Tribalism is the curse of Africa,’ said the first Zambian president, Kenneth Kaunda. Like the other founders of the Organization of African Unity, he wanted to achieve the existing colonial borders, he wanted to promote a new sense of togetherness between the ethnic groups. The hope was to overcome tribalism within the new nations and ultimately to find a pan-African identity, according to the motto’ unity in diversity and diversity in unity’.

But tribalism – discrimination based on ethnic origin – soon found its way back into the new African societies. The former colonial powers continued to secure influence and access to raw materials by supporting local elites. Where once the national movements had a charismatic leader, they often developed personality cults. Initial multi-party systems usually turned into one-party rule, which supported the autocrat. The most brutal power was the military, which relied on a European-trained officer corps and, in many cases, was dominated by just one ethnic group.

Even the best political appointments and lucrative businesses were allocated to those associated with the ruling power and people of their own ethnic group, including civil jobs like offices for judges and public prosecutors. It was not about the good of the nation. It was about bringing one’s ethnic group to power.

That is the fertilizer on which corruption thrives, feeding the hatred of the marginalized. New ethnic conflicts soon followed, from the Biafra war at the end of the sixties to the genocide in Rwanda in the mid-nineties.

Today, my home country of Ethiopia is at the center of ethnic conflicts. Ethiopia is the only country on the African continent that was never a European colony. Two generations after the founding of the Organization of African Unity, unfortunately, a student in Addis Ababa can no longer say, ‘I am an Ethiopian’ without fear. He is expected to answer: ‘I am Oromo.’ Or ‘Amhara’ or ‘Tigray’ or “Gurage” or “Afar” or ‘Somali’ or any other of the more than eighty ethnic groups that call Ethiopia their home. The standard and unifying aspects are no longer emphasized, but the divisive and discriminatory ones. Ethiopia describes itself in its 1995 constitution as an ‘ethnic federation.’

Dr. Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate

Only by belonging to one of the country’s ethnic groups can one become an Ethiopian citizen. This is unique. Many countries, such as Nigeria or India, have far greater ethnic differentiation than Ethiopia. In all democratic constitutions worldwide, the people are the common sovereign. Not in Ethiopia: Here, we are only talking about the sovereignty of the different peoples and ethnic groups.

‘When the awareness of the unity of humanity dwindled, clans and peoples and strife without end,’ wrote the Chinese sage Lao-Tse more than 2500 years ago. Ethiopia is a country whose culture is founded on the Bible. It is the original home of all Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

What the Chinese sage called the ‘consciousness of the unity of mankind,’ the apostle Paul expresses in Christian language: ‘There are no longer Jews and Greek, not slave and free, male and female; for you are all one are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3,28). For me, this is the basis for a multiethnic society, as it has been in Ethiopia for centuries, living together peacefully. But what does ‘ethnic federation’ mean?

The Burish nationalist politician Daniel François Malan became Prime Minister of South Africa in 1948 and installed the notorious system of racial segregation, the apartheid regime. ‘Apartheid’ means “separateness”. Malan himself defined this regime as an ‘ethnic federation.’ We can see similarly devastating consequences of political segregation by ethnicity in Ethiopia today: division and hatred that escalate into civil wars and brutal and bloody massacres against other ethnic groups, including mothers

and children.

Inhuman incitement, today especially against the Amhara ethnic group, both by Ethiopian politicians and in social media, erodes the threshold of aggression. People who have lived together as neighbors for generations are now being compared to a ‘virus’ that needs to be eradicated, with animals that need to be slaughtered, or to weeds that should be uprooted. And in Ethiopia, it has not stopped at threats and incitement: We mourn the loss of tens of thousands of victims of so-called ‘ethnic cleansing.’

Although the ruling Oromo Prosperity Party, governed by Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, implies that the Oromo are the largest ethnic group, this has yet to be confirmed by independent demographic institutions. One of the largest ethnic groups, the Amhara, is confronted with the historically false accusation of having dominated and subjugated the other peoples in Ethiopia’s long history. The three-thousand-year history of the empire is said to have been an Amhara history – which does not correspond to the facts. Whatever one may accuse the Ethiopian imperial dynasty of, its goal was never the dominance of one ethnic group but the unity and independence of the nation. That is why the ruling dynasty’s marriage policy was designed to unite the people. In the long history of the Solomonic dynasty, there was never a ruler who belonged to only one particular ethnic group. The old name of Ethiopia is Abyssinia. It is derived from the Arabic word ‘Habesha,’ meaning mixed race.

Because that is what Ethiopia has always been and still is today: a melting pot of different peoples and ethnicities. Today, however, Ethiopian identity cards assign each citizen to a specific ethnic group, usually that of their father. This entry can make the difference between life and death in the event of conflict. The current Ethiopian government of Abiy Ahmed shows little interest in uniting the country or calming the conflicts. On the contrary, it pours gasoline on the fire of anger and hatred between the ethnic groups.

The world public, however, mostly looks away. Prime Minister Abiy started 2018 with rich advance praise for his office. I also had high hopes for him. He promised peace, unification of the country, economic upturn, and the end of the ‘apartheid constitution.’ He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the end of the decades-long conflict with neighboring country Eritrea. Not least, the excessive international enthusiasm at the beginning of his time in government encouraged the prime minister in his uncompromising course.

Today, Abiy plays one ethnic group off against the other to maintain his power. He seems to have lost touch with reality. Abiy sees himself as the founder of a new Cushitic Oromo empire. He is currently building a new palace, a kind of luxury playground totaling five hundred hectares, ‘bigger than Windsor, the White House, the Kremlin, and the Forbidden City put together,’ as the magazine Africa Confidential’ has noted. It is to be an urban amusement park for the elite on a hill above the capital, with a luxury hotel, conference center, and luxury residential complexes.

A cable car will be used to transport residents and guests back and forth. The construction costs are estimated at ten billion dollars is the estimated construction cost. This corresponds to almost the entire annual national budget of Ethiopia. Yet more than twenty million people, one-sixth of the population, depend on food rations again. The tender plant of the economic upswing has long since withered. The Ethiopian national currency, the birr, has just been devalued thirty percent.

The supply situation for the population continues to worsen. War and poor harvests have been followed by famine, and hundreds of thousands of people are fleeing from rampant violence. In addition to ethnocentric politics, poor governance and corrupt elites are the main reasons for persistent hardship and misery in many African countries. The many billions in development aid that flow into Africa year after year have hardly improved the living conditions of the people on the continent:

A large proportion of this money flows into the pockets of corrupt elites, who use it to finance luxury flats in Paris or London or fill Swiss bank accounts. What is needed is an international control body that monitors the allocation of funds according to strict criteria. The allocation of funds according to strict criteria. The most important criterion should be good governance. With ethnocentric tyrant rulers who trample on human rights in their countries, who do not uphold the rule of law, provoke ethnic conflicts, and are generally only interested in increasing their wealth, there must be no more cooperation.

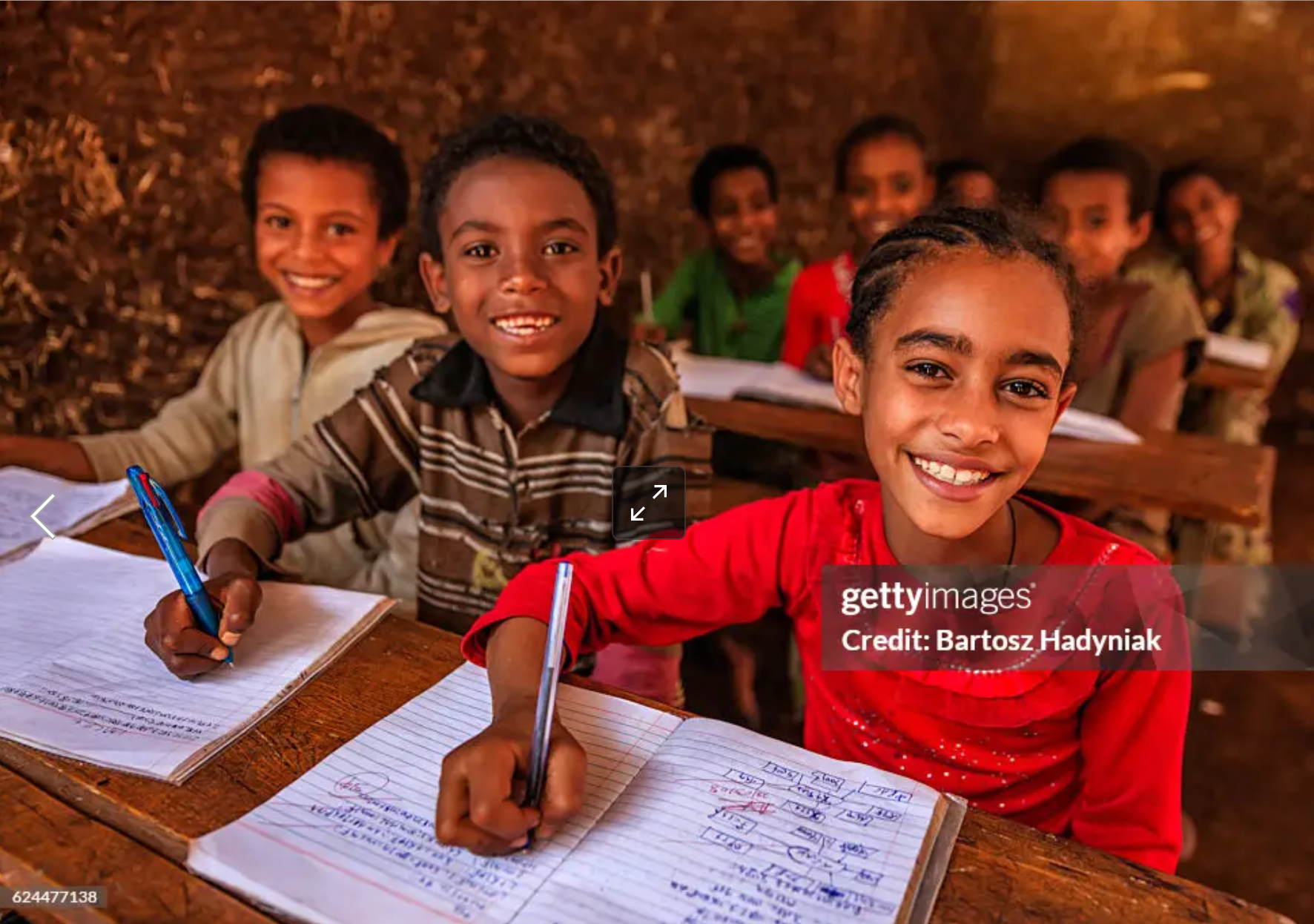

It is in Europe’s interest to give young people in Africa, particularly, the prospect of a better life in their home countries. More than half of today’s 1.3 billion Africans are under the age of twenty. Anyone visiting Africa today is impressed by the omnipresence of the smartphone and the social media activities of young Africans. Thanks to digital media, young people are connected to the globalized world. Their ambitions are orientated according to the prosperity of industrialized countries, which has become a global benchmark. This has an impact on all areas of life, especially on consumer behavior and migration.

Young citizens with nothing to lose, only prospects, are to rebel and cannot be stopped in the long term. Their numbers in Africa are constantly increasing. The main reasons for this are ethnocentric politics, poor governance, and corrupt elites.

Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate was born in 1948 into a family belonging to the Solomonic dynasty. He came to Germany as a student. Today, he lives in Frankfurt am Main as a management consultant for Africa and the Middle East. He is a bestselling author; His latest book is ‘Deutsch vom Scheitel bis Zur Sohle’ (‘German from head to toe’) (The Other Library).

Source: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

This article was first published in the German newspaper “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” on 12.08.2024. It is a translation from German into English language.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in articles published by East African Review are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the perspectives of the editorial team or East African Review as an organization. The publication of any opinion piece does not imply endorsement by East African Review. We encourage our readers to critically assess the content and form their own opinions. We welcome your feedback and reflections; please share them in the comments below or email us at eastafricanreview@gmail.com